· Updated: · GoodSleep Team · science-of-sleep · 9 min read

What is REM Sleep and Why is it Crucial for Your Brain?

REM sleep was discovered by accident in 1953 when graduate student Eugene Aserinsky noticed that sleeping infants’ eyes moved rapidly at certain times during the night. This observation, made in Nathaniel Kleitman’s sleep lab at the University of Chicago, revolutionized our understanding of sleep. What had been considered a passive, uniform state turned out to be a dynamic process with distinct stages—and REM sleep emerged as perhaps the most fascinating of them all.

During REM sleep, your brain becomes almost as active as when you’re awake, yet your body lies essentially paralyzed. This paradox—an active mind in an immobile body—gives REM its alternative name: paradoxical sleep. Understanding what happens during this stage reveals why it’s essential for cognitive function, emotional health, and overall well-being.

To see how REM fits into a full night’s rest, refer to our Ultimate Guide to Sleep Cycles.

The Physiology of REM Sleep

Brain Activity

During REM sleep, electroencephalogram (EEG) readings show brain wave patterns remarkably similar to wakefulness. The brain produces low-amplitude, mixed-frequency waves—a stark contrast to the slow, synchronized delta waves of deep sleep.

Several brain regions become highly active during REM:

The limbic system, including the amygdala and hippocampus, shows increased activity. These structures are central to emotion and memory, which may explain why REM dreams are often emotionally charged and why this stage is critical for memory consolidation.

The visual cortex activates despite closed eyes, generating the vivid imagery we experience in dreams.

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for logical thinking and self-awareness, shows reduced activity. This may explain why dreams often lack logical coherence and why we rarely question bizarre dream events while they’re happening.

The Paralyzed Body

While the brain races, the body enters a state called atonia—temporary paralysis of voluntary muscles. The brainstem sends signals that inhibit motor neurons, preventing you from physically acting out your dreams.

This paralysis affects the limbs and torso but spares the diaphragm (allowing breathing) and the eye muscles (producing the characteristic rapid eye movements). The eyes dart back and forth, up and down, in patterns that sometimes correlate with dream content—as if watching the dream unfold.

Atonia is a protective mechanism. Without it, people would physically act out their dreams, potentially injuring themselves or their bed partners. In REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), this paralysis fails, and people do act out dreams—often violently. RBD can be an early warning sign of neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s.

Autonomic Instability

Unlike the calm, steady state of deep sleep, REM sleep brings autonomic instability:

- Heart rate becomes irregular and can increase

- Blood pressure fluctuates

- Breathing becomes faster and more erratic

- Body temperature regulation is impaired (you don’t shiver or sweat effectively)

- Men experience penile erections; women experience clitoral engorgement (unrelated to dream content)

This physiological activation reflects the brain’s heightened state during REM.

When Does REM Sleep Occur?

REM sleep follows a predictable pattern across the night. The first REM period typically occurs about 90 minutes after sleep onset and lasts only 10-15 minutes. As the night progresses, REM periods become longer and more frequent.

Early night: Dominated by deep sleep (N3), with short REM periods Late night/early morning: Dominated by REM sleep, with periods lasting 30-60 minutes

This architecture explains several common experiences:

- Morning dreams are more memorable because you’re more likely to wake from a long REM period

- Sleep deprivation causes “REM rebound”—when you finally sleep, you enter REM faster and spend more time in it, as if the brain is catching up on missed REM

- Alcohol suppresses REM early in the night, leading to REM rebound later and often vivid, disturbing dreams as the alcohol wears off

Adults typically spend 20-25% of their sleep time in REM—about 90-120 minutes per night. This percentage is much higher in infants (50%) and decreases with age.

The Functions of REM Sleep

Memory Consolidation

Sleep plays a critical role in memory, and different sleep stages appear to consolidate different types of memory. REM sleep is particularly important for:

Procedural memory: Skills and “how-to” knowledge. Studies show that learning a new motor skill (like a finger-tapping sequence) improves after sleep, and this improvement correlates with time spent in REM. Musicians, athletes, and anyone learning physical skills benefit from adequate REM sleep.

Emotional memory: REM sleep helps process and integrate emotional experiences. The amygdala is highly active during REM, and this stage appears to help separate the emotional charge from memories—you remember what happened, but the raw emotional intensity fades.

Creative problem-solving: REM sleep may facilitate creative insights by allowing the brain to form novel associations between disparate pieces of information. The reduced prefrontal activity during REM may actually help by loosening the constraints of logical thinking.

A study at Harvard found that people who entered REM sleep during a nap were 40% better at solving creative word puzzles than those who napped without REM or stayed awake.

Emotional Regulation

REM sleep functions as a form of overnight therapy. During this stage, the brain reprocesses emotional experiences from the day in a neurochemical environment with reduced norepinephrine (a stress-related neurotransmitter).

This allows emotional memories to be “replayed” without the full physiological stress response. Over successive nights, the emotional intensity of memories diminishes while the informational content remains. This is why “sleeping on it” often helps with emotional problems—and why sleep deprivation makes people emotionally volatile.

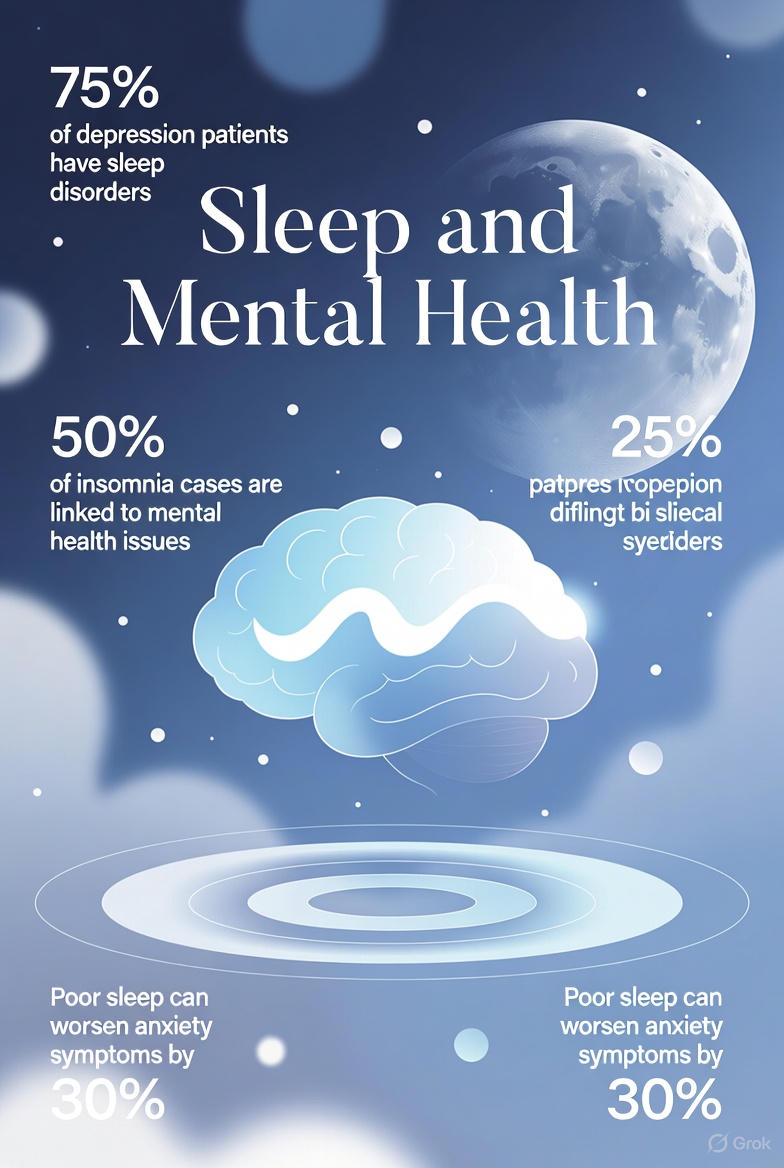

Research by Matthew Walker at UC Berkeley demonstrated that REM-deprived individuals showed a 60% increase in amygdala reactivity to negative images compared to those who slept normally. Without adequate REM, the brain loses its ability to regulate emotional responses.

Brain Development

The high proportion of REM sleep in infants and young children suggests it plays a crucial role in brain development. During REM, the brain may be:

- Strengthening neural connections

- Pruning unnecessary synapses

- Developing visual and sensory processing systems

Premature infants spend up to 80% of their sleep in REM. As the brain matures, this percentage gradually decreases to adult levels.

Neural Maintenance

Recent research suggests REM sleep may serve important maintenance functions:

Synaptic homeostasis: During waking hours, synaptic connections strengthen as we learn and experience. REM sleep may help reset these connections, preventing the brain from becoming “saturated.”

Glymphatic clearance: While the glymphatic system (the brain’s waste-clearance pathway) is most active during deep sleep, some clearance continues during REM.

Dreaming and REM Sleep

REM sleep is strongly associated with vivid, narrative-style dreaming, though dreams can occur in other sleep stages as well.

Characteristics of REM Dreams

REM dreams tend to be:

- Vivid and visually detailed

- Emotionally intense

- Narrative in structure (they tell a story)

- Bizarre, with impossible events accepted as normal

- Difficult to control (unlike lucid dreams)

The content of REM dreams often incorporates recent experiences, emotional concerns, and fragments of memory. The “day residue” phenomenon—dreaming about events from the previous day—is common.

Why We Dream

Despite decades of research, the function of dreaming remains debated. Theories include:

Threat simulation: Dreams may have evolved to simulate threatening scenarios, allowing us to practice responses without real danger.

Memory consolidation: Dreams may reflect the brain’s process of sorting and storing memories.

Emotional processing: Dreams may help process and integrate emotional experiences.

Random activation: Some researchers argue dreams are simply the brain’s attempt to make sense of random neural activity during REM.

These theories aren’t mutually exclusive—dreaming may serve multiple functions.

What Happens Without Enough REM Sleep?

Cognitive Impairment

REM deprivation impairs:

- Learning new skills

- Creative problem-solving

- Memory consolidation

- Attention and concentration

Studies in which subjects were selectively deprived of REM (by waking them each time they entered REM) showed significant cognitive deficits even when total sleep time was maintained.

Emotional Dysregulation

Without adequate REM sleep, emotional regulation suffers:

- Increased irritability and mood swings

- Heightened anxiety

- Reduced ability to read others’ emotions accurately

- Impaired social judgment

People who are REM-deprived often report feeling emotionally “raw” or reactive.

REM Rebound

When REM sleep is restricted, the brain compensates with REM rebound—entering REM faster and spending more time in it when sleep is finally allowed. This suggests the brain has a specific need for REM that must be met.

Alcohol, many sleep medications, and cannabis all suppress REM sleep. When these substances are discontinued, intense REM rebound can cause vivid, often disturbing dreams.

Factors That Affect REM Sleep

Age

REM sleep percentage decreases across the lifespan:

- Newborns: ~50%

- Children: ~25-30%

- Adults: ~20-25%

- Older adults: ~15-20%

This decline may contribute to age-related changes in memory and emotional regulation.

Substances

Alcohol: Suppresses REM in the first half of the night; causes REM rebound later

Caffeine: Can reduce REM sleep, especially when consumed late in the day

Cannabis: Suppresses REM sleep; cessation causes intense REM rebound with vivid dreams

Many antidepressants: SSRIs and SNRIs suppress REM sleep, which may actually contribute to their therapeutic effect in depression

Sleep medications: Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (like zolpidem) can reduce REM sleep

Sleep Disorders

Sleep apnea: Breathing interruptions fragment sleep and reduce time in REM

Narcolepsy: Characterized by abnormal REM regulation, including entering REM immediately upon falling asleep

REM sleep behavior disorder: Failure of the normal REM paralysis, allowing people to act out dreams

Lifestyle Factors

Sleep deprivation: Causes REM rebound when sleep is restored

Irregular sleep schedule: Disrupts the normal progression of sleep stages

Stress: Can increase REM sleep and dream intensity (possibly reflecting increased emotional processing needs)

Optimizing Your REM Sleep

While you can’t directly control which sleep stage you enter, you can create conditions that support healthy REM sleep:

Get enough total sleep: REM periods are longest in the final hours of sleep. Cutting sleep short disproportionately reduces REM time.

Maintain a consistent schedule: Regular sleep timing supports normal sleep architecture.

Limit alcohol: Especially in the hours before bed, as it suppresses REM.

Manage stress: Chronic stress can disrupt sleep architecture. Relaxation techniques before bed may help.

Review medications: If you’re taking medications that affect sleep, discuss with your doctor whether alternatives exist.

Treat sleep disorders: Conditions like sleep apnea fragment sleep and reduce REM. Treatment can restore normal sleep architecture.

Assessing Your Sleep

If you’re concerned about your sleep quality or suspect you’re not getting enough restorative sleep, consider:

- Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): Evaluates overall sleep quality

- Epworth Sleepiness Scale: Measures daytime sleepiness, which can indicate poor sleep quality

- Sleep Cycle Calculator: Helps time your sleep to wake at the end of a sleep cycle

Consumer sleep trackers claim to measure REM sleep, but their accuracy is limited. True sleep staging requires EEG monitoring. However, trackers can provide useful information about total sleep time and sleep consistency.

The Bottom Line

REM sleep is far more than “dream time.” It’s an active, essential process during which your brain consolidates memories, processes emotions, and performs critical maintenance. The paralyzed body and racing mind of REM sleep represent one of the most remarkable states in human physiology.

Prioritizing sleep isn’t just about avoiding tiredness—it’s about giving your brain the REM sleep it needs to learn, remember, and maintain emotional equilibrium. When you cut sleep short, you’re disproportionately cutting REM, with consequences for cognition and emotional well-being that extend far beyond feeling tired.